Le Printemps

Trace the history of the department store Printemps and discover antique and unseen photographs

It’s in 1852 that appears the first department store in Paris : Au Bon Marché, initiated by Aristide and Marguerite Boucicaut . Only a tailoring shop for men at the beginning, the store gets bigger throughout the years and absorbs the buildings next door.

The Printemps construction by Paul Sédille

The Printemps – created in 1863 by Jules Jaluzot (1834 – 1916) – is another example of a department store appearing in the second half of the 19th century. Son of a notary, having studied in the école de Saint-Cyr from 1854, Jules Jaluzot suddenly changes his professional path for commerce. He started in a first time as an assistant in the Jeune Orpheline and Villes de France stores then becomes department chief in the Bon Marché. His wedding brings him a dowry allowing him to invest in the construction of a bulding rue du Havre covering the corners of the Boulevard Haussmann and the rue de Provence, then from 1874, the rue de Provence. This location is strategic as it’s in the new Opera district, then arising, and near the Saint-Lazare station which allows to aim a provincial or foreign clientele.

The building was conceived by the architect Jules Sédille (1806 – 1871) and his son Paul to welcome on the ground floor, mezzanine floor and basement, his new novelties store : the Printemps store, whil the other floors were inhabited. Quickcly the Printemps becomes one of the three most important department stores of Paris, in competition with the Bon Marché and the Louvre stores. Its major difference lies in the fact that it starts with a relatively large store and not a modest shop gradually extended.

On the 9th of March 1881, around 5 am, the Printemps is destroyed by a terrible fire. Jules Jaluzot, very audacious, asks his clients to invest and found a new company Au Printemps of which he is the main interested and manager. He also asks his employees by proposing a profit interest if they invest in the help for the reconstruction.

The reconstruction was givent to Paul Sédille (1836 – 1900) now famous for his realizations of the basilica Jeanne d’Arc in Domrémy or the pavillion of the Creusot factories in the 1878 World Fair and his masterful use of the Venitian Renaissance polychromatic style during the same event.

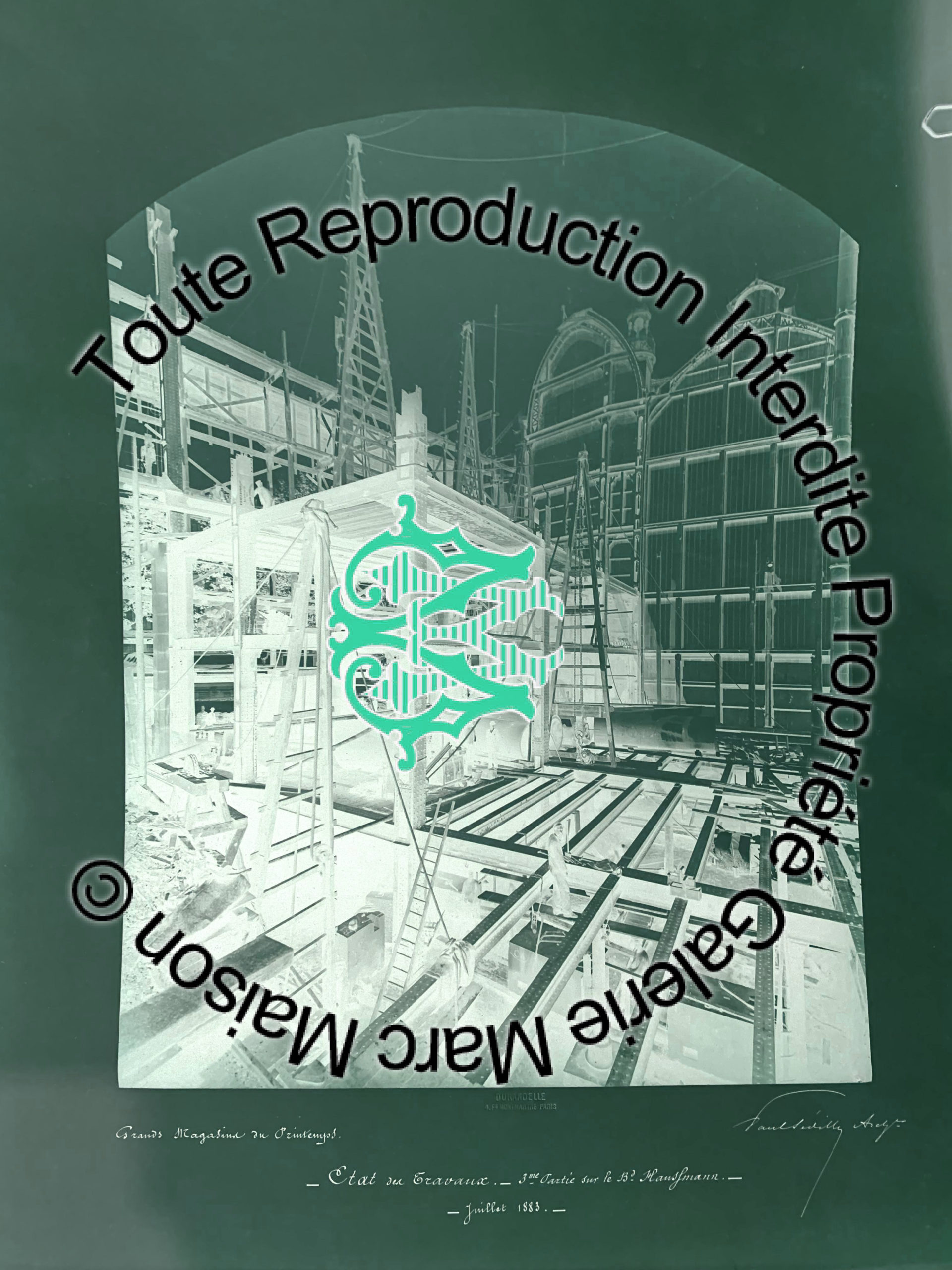

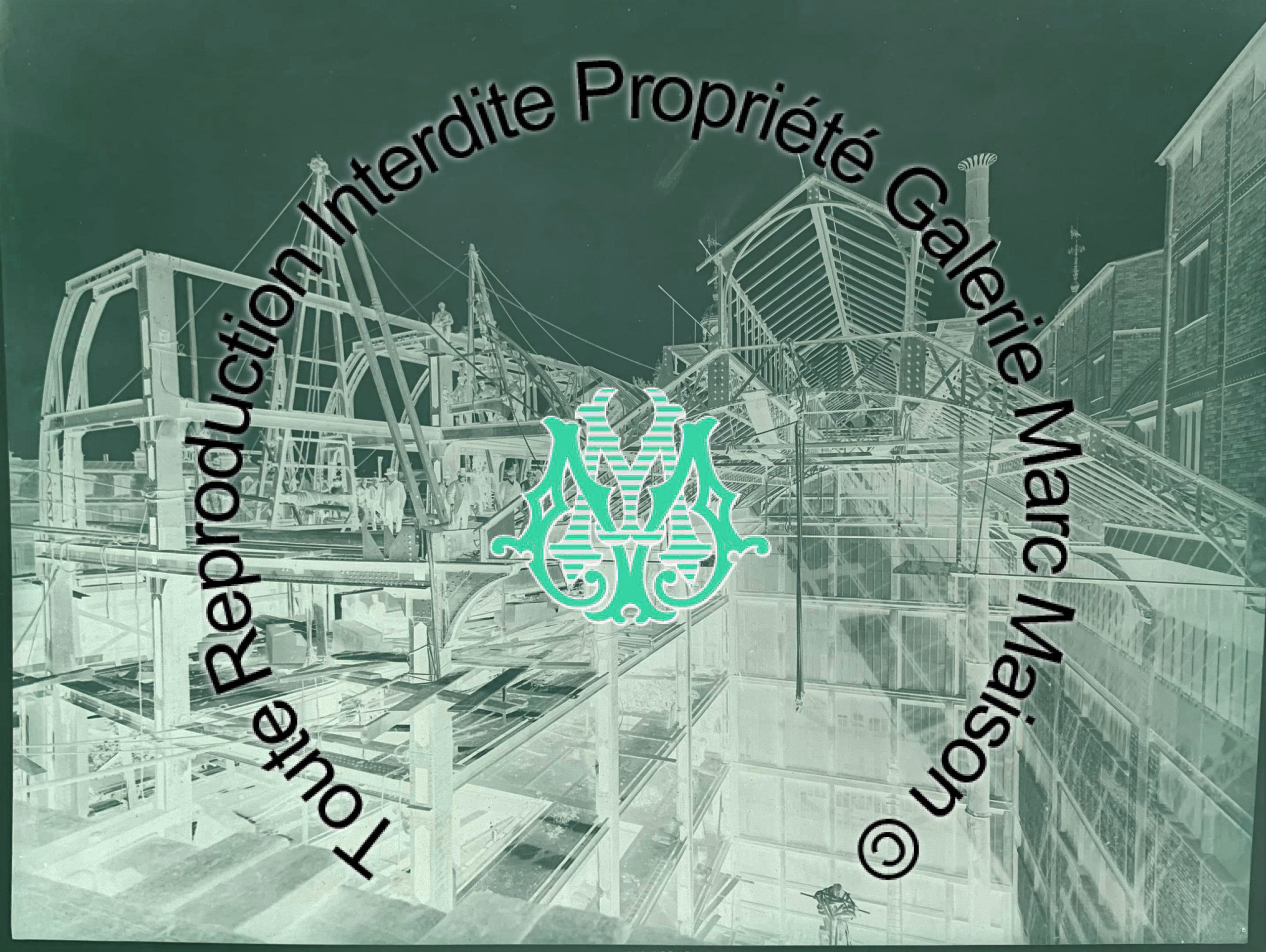

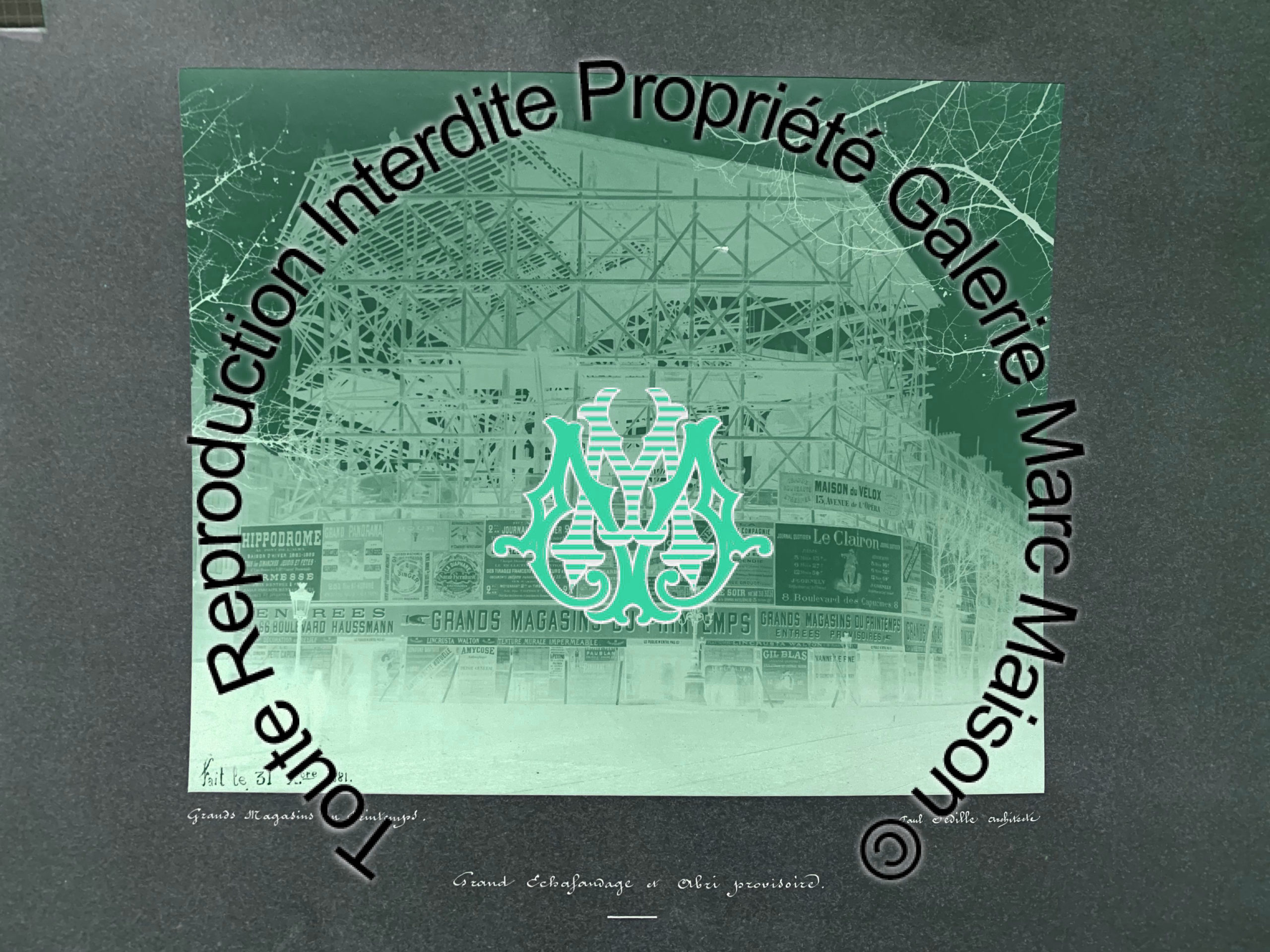

For the making of this construction which spreads between 1881 and 1889, a precise programm was given to the architect, « to rebuild the stores on a plan including now the whole block envelopped by the boulevard Haussmann, the rue du Havre, the rue de Provence and the rue Caumartin, then proceed by construction lot, starting with facade on the rue du Havre, to temporarly continue the sell in the inferior parts of the building that the fire hasn’t completely destroyed».

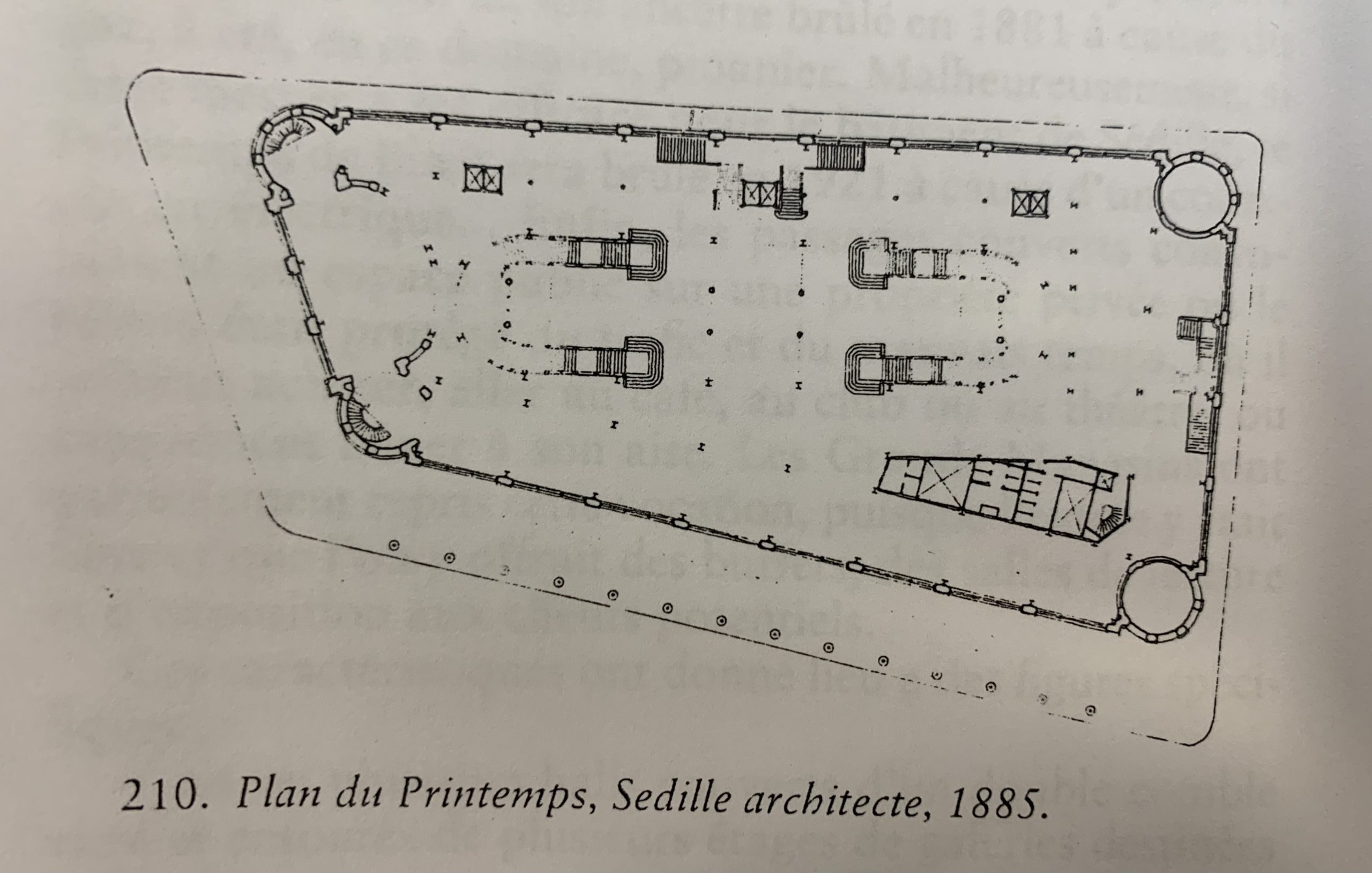

The block on which the new Printemps building was going to be built was an irregular trapezium of 2950 sq. It’s especially thanks to the use of rotondas on each corner of the building that create an optical illusion that these irregularities were hidden. These rotonda are the only elements made of masonry.

The work site was not without constraints and force the architect to challenge his immagination and his ideas of innovations. Indeed, the building on the rue Caumartin side saved by the fire, was used before for the tailoring, and now for the sell continuity. The building site was then divided into five blocks to facilitate the cohabitation between the commercial activity and the works.

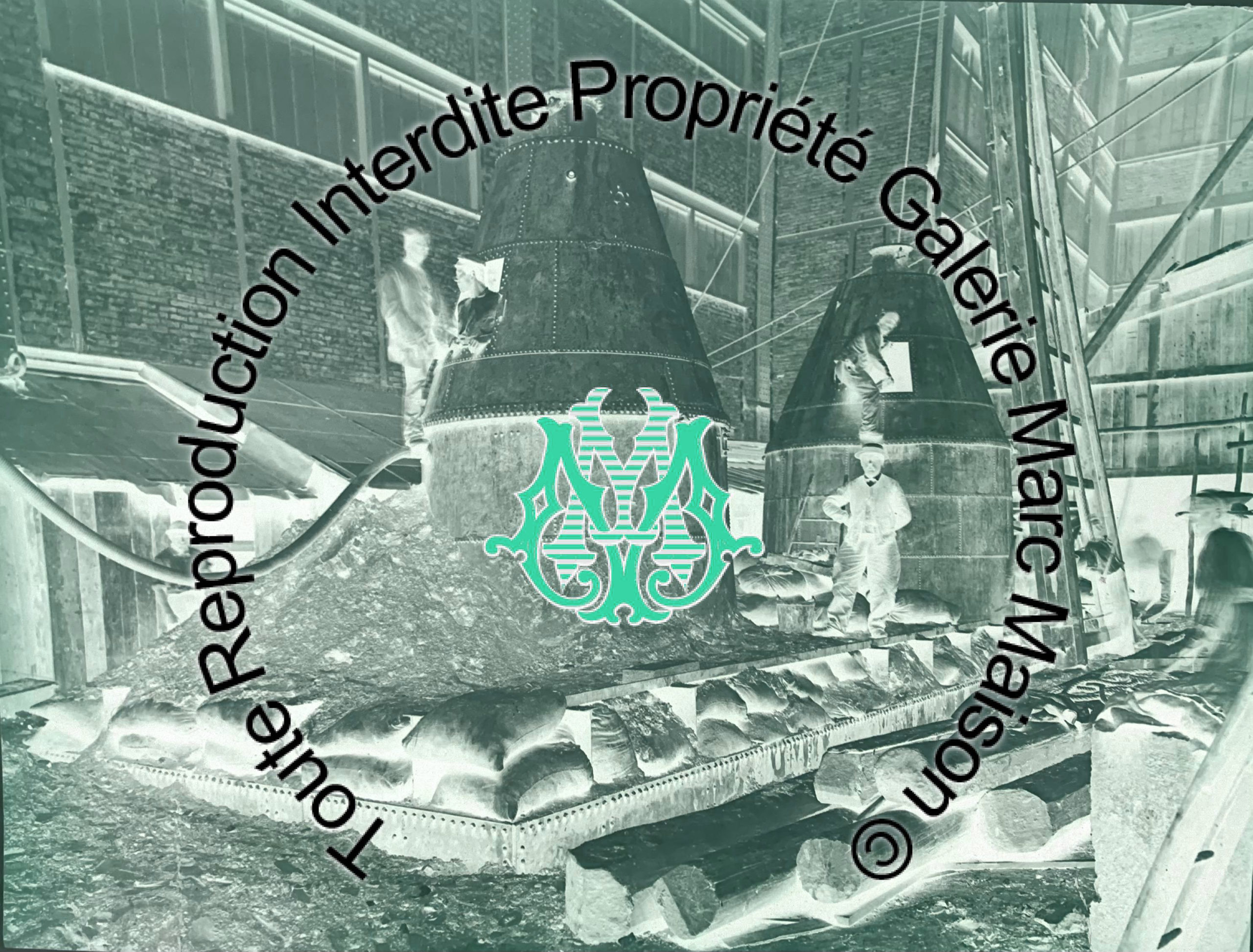

Moreover, the block was uppon a clay soil, not resistant because of the proximity with an infiltration table. Paul Sédille, precursor and aware of the new technicals, decided to run the foundations helped by crats in which compressed air was continually blown. This method was, until then only used for the construction of bridges, it was for the first time applied to an architectural work with the Printemps construction. Thus, on these concrete massives of which the sides were about 2,40m, were risen pillars forming the whole metallic structure of the building.

Sédille’s choice for iron for the structure, was motivated by the constraint of a 9 floors building which had to support important weighs with less masonry possible to keep the light in.

Thereby, the use of a metallic structure allows the construction of a vast building with monumental facades pierced by many and large windows favouring light and spaces.

From the 1850’s, many architectes had already used iron for buildings realizations – opposite idea to the Beaux-Arts teaching – like Paxton with the Crystal Palace (1851, today destroyed), Baltard with the covered market (1853) or later Boileau in the Bon Marché (1872).

The metallic structure is also used for the interior walls of the facade, which makes the Printemps one of the first building with a non supporting facade.

Thus, the external walls, not caring anything, are simply decorative. All the masonry is supported by the metallic construction of which the stone only forms an envelope, allowing to speak of a true technical achievement.

It is decided that the main facade should be the one on the rue du Havre side because of its less important dimensions. This facade, emblem of the building, takes the composition from the department store’s facade La Belle Jardinière, made in 1867 by Henry Blondel.

Convinced by the polychromy, Paul Sédille makes the main facade of the Printemps of granite and white marble flanked by two rotondas surmounted by domes.

It is adorned with four sculpture by Henri Chapu depicting the four seasons and larges polychromatic mosaic bands on which we can read « Au Printemps » risen with gold, drawn by the architect and made by Gian-Domenico Facchina in 1883.

The side facade on the boulevard Haussmann is pierced with large windows on the ground floor to remind the commercial vocation of the building.

The interior is mainly inspired by the covered passages but also the oriental bazaar, churches and Renaissance palaces. Influenced by the Rationalist architectural theories of Viollet-le-Duc, Sédille lets the metallic structure appear on the building inside.

He creates on the ground floor, a important central nave of 50 meters long, 12 meters large and 20 meters high in the ground direction from the rue du Havre to the rue Caumartin, with an important originality : the ceiling with stained-glass was destined to light up and aerate the building.

The ground floor, and three other floors, were dedicated to the selling, while we found on the fourth the checkout and the province and foreign offices. The last two ones under the attic were used as storehouse, kitchen and refectory. The basement was destined to the reception and expedition but also the installation of the many mecanical material for the heating system, water and electric lightning. This lattest, is parti of the other element of modernity as we could count 160 Jablohkov hearths, new lamps with bow and 112 incandescence lamps. Thus, the Printempss store was in advance compares to the city which will wait until 1889 to install the public electric lighting.

Other transformations were brought next to the architecture in 1904 by René Binet, and in 1907 with the project of a second building. Nevertheless, the Printemps by Sédille was quickly considered as the department store model thanks to its layout which represents a fonctional space. Moreover, art and architecture historians recognize it today as department store prototype but also as the modern industrial building.

In his book Au bonheur des Dames, published in 1883, Emile Zola tells the story of Octave Mouret director of the department store Au Bonheur des dames, inspired by the Bon Marché. In the following description, he describes the architecture of the fictive department store Au Quatre Saisons, inspired by the Printemps of Sédille :

« It was like a station nave, surrounded by handrails of two floors, cut with suspended staircases (…), iron bridges thrown on the emptyness, run straight, very high ; and all this iron put there, under the white light of the windows, a modern architecture from a dream palace, a Babel piling up floors, widening the rooms, opening views on other floors and other rooms to the infinite. From the rest, iron ruled eveywhere, the young architect had the honesty and the courage to not disguise it under a layer imitating the stone or the wood. Bellow, to not harm the merchandise, the decoration was sober, large plain parts of neutral colors ; then as the metallic structure ascended, the colonms capitals became richer, the nails formed flowers, the consoles and corbels received sculptures ; up finally, paintings break out in the middle of gold prodigality, gold floods, gold wealths…» Au bonheur des dames, Emile Zola